At a time when Western society has become diametrically opposed to the “Great Man” theory of history, I find that we are discovering new and interesting ways to sacrifice the good and the known in the Quixotic pursuit of perfection. Mankind has always sought to make sense of the seemingly random drivers of progress by attributing causation to a higher power. For the first civilizations that left us written accounts, there were attributions of gods and demi-gods: from Prometheus stealing fire from the gods, Achilles leading the Sack of Troy, or Moses calling upon Yahweh to close the Red Sea upon the Egyptians. The gods and the mortal foils that became legends in the retelling were the drivers of our inherited civilization and culture.

As history evolved from the fog of millennia, and attribution landed more upon flesh and blood men and women, our need for the legendary never waned, it merely transitioned from the gods to those people who drove the story like Napoleon and Caesar, or Catherine de Medici and Joan of Arc. While credit for the direction of history landed on mortals who walked the earth among us, the retelling made legends out of men and women who ate, defecated and died just like the mortals I see today.

I grew up in a community with a living demi-god. In Indiana, our gods sprang from polished hardwood with the same rapidity as a sharp dribble. In Bedford, Indiana, our demi-god went by a single name, as most do, and that name was Damon.

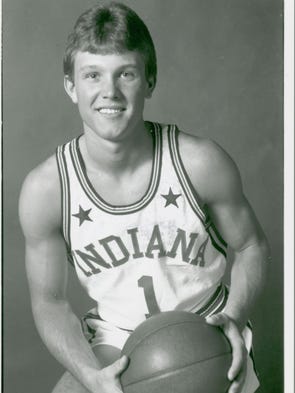

Damon Bailey was the greatest high school basketball player in Indiana history. In the halls indicative of the 1970s era building that housed Bedford North Lawrence High School, there was a mundane concrete staircase that opened up into a shrine, wherein an 18-year-old Damon Bailey stood in a life-sized photograph of an eager kid looking up with a basketball in his hand and the #1 jersey for the Indiana All-Stars that signified his status as Mr. Basketball in a state where no higher honor exists. The banner from his 1990 state championship still waves over the floor where I shot basketballs in gym class with much less success. In small plastic letters in a shadow case, his scoring record of 3134 career high school points is still seen by every entrant through the southern doors of the BNL Fieldhouse.

In front of his elementary school, there is a life-sized limestone carving of a 12 year old Damon shooting a foul shot. This statue didn’t seem out of the ordinary when I was growing up, because it was as much a part of the landscape as the hills that housed my hometown, but as I grew older, the realization of absurdity finally dawned on me that any 12-year-old had a statue created of his likeness.

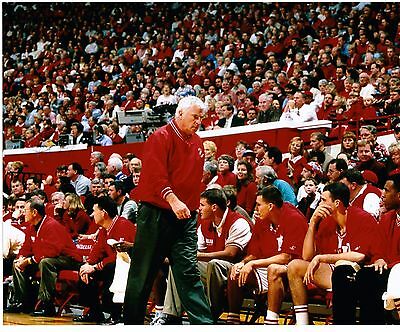

Damon Bailey’s ascent to Olympus started with a book chronicling one of the worst seasons that another legend from the previous generation ever had to endure. That legend’s Christian name was Robert Montgomery Knight, but when he wasn’t being referred to as “The General”, he was known simply as Bobby. Bobby Knight coached IU to three national championships, and he had a winning record over every school in the Big Ten not named Purdue. However, Season on the Brink, was a book that showed in vivid detail, the reality behind a legend. In that book, a Bobby Knight said that Damon Bailey, at the age of 13 would be the starting point guard on a team with no less a starting point guard than Steve Alford.

Bobby Knight was an incredible hardass. He demanded total submission from his players, and used tactics to deliver that submission that could be most generously called “tough love” but was also accurately deigned psychological abuse. He had a moral compass that only pointed one direction, and often bulldozed everything between point A and B. His players graduated with degrees, and he took immense pride in the fact that his players were student-athletes, a quaint notion at a time when players are looked at more as unpaid professionals than students at all.

The General broke the spirit of more than one player in this 25+ years on the bench in Assembly Hall, but he created a fraternity of survivors that showed him deference and loyalty regardless of their post-collegiate successes.

As a 12-year-old, I watched a revolution as unthinkable as the Communists overthrowing the Romanov Czar, when Bobby Knight was removed as IU’s coach in the culmination of the most poignant Greek cum Hoosier tragedy ever written. The details are disputed and largely unimportant, but the first day that Bobby Knight was no longer prowling in front of the bolted down chairs of Assembly Hall was an unimaginable epoch shift.

Seeing that legend fall from grace had a lasting impact on my thoughts on the power of narrative and the transience of power generally. Getting to know one of Bobby’s in-laws well, I realized that for all his victories and legions of crimson clad disciples, he was just a man. Today Bobby is an old man, suffering with the inevitability of age on his body and mental acuity.

Status as a legend is no shield against the ravages of our shared mortality.

I got to see Damon up close, as a man who was a god from prepubescence evolved into a basketball dad in middle age. Being a Purdue fan in Bedford was tough, as there were no greater apostasy that to root against Damon and the General, so Damon’s effect as a living god was diminished if not completely muted on me.

The day after he’d blown a knee in one of the many barnstorming tours he used to make across the State of Indiana, he walked into the office in the athletic department where I’d somehow managed to take up residence as a “student assistant” and made a comment about my Purdue sweatshirt. “Moorman, why don’t you get an IU sweatshirt instead of that terrible thing?” I looked back in all the earnestness of a true Boilermaker believer and said, “Damon, why aren’t you still in the NBA?”

I’ve always imagined the confused look of Goliath the instant after a well placed stone from a shepherd boy hit him in the forehead.

On that day, I saw that look on the face of a legend, and this son of David caused it.

No one ever talked back to Damon. It was as anathema as cursing in front of the Pope.

In that moment, as I quickly scurried out from the blast zone as my athletic director nearly brained me for insulting our most important donor, I realized the truth about legends.

Behind the façade and the propaganda of their partisans, they are individuals who eat, defecate and die just like you and me.

Legends, like the local gods of ancient civilizations, can have immense power within their spheres of influence. Those spheres can be as small as a family unit or a small town, and they can span the globe like the legend of America’s Founding Fathers. Regardless of reach, legends are only as strong as their perceptions in the minds of those who come after them.

As I’ve grown in age and experience, I’ve encountered many small sphere legends. My grandfather was one, the seemingly immortal Gene Moorman. He made a small fortune selling hot dogs, root beer and Christmas trees, and he lived fast and free in a way that made him a legend to the clock-bound wage earners of General Motors and Delco Remy in Madison County, Indiana.

They say that no man is a great man to their chambermaid, and Gene proved that to me. For all the people who knew that I was Geno’s grandson, and talked about how much fun it must be to have him as a granddad, few people knew the logistical reality of keeping that legend fed, watered, and out of harm’s way.

Gene was a legend for his defiance, and never saw himself as more than “a feller who wanted to find some fun trouble to get into.” For a living legend to be somewhat indifferent about how he is perceived doesn’t heap extra work upon the propaganda department. That was a blessing.

My brother and I got to see Grandpa for what he was, the good and the bad, and knowing him as a flawed man yet loving grandfather meant that we were never forced to measure ourselves to a mythical standard that started with a man and grew into an idealized legend.

To measure oneself against a legend can seed within the hearts of great men insecurities on par with those of an acne faced 13 year old attempting to “get the girl.”

Caesar was said to have wept at the grave of Alexander the Great, for his achievement of sole control of the Roman Empire was but a trifle compared to the man who conquered from the Aegean to the Ganges before the age of 33.

If comparison is the death of joy, then measuring oneself against a legend will be the root of one’s most virulent insecurities.

Having not been a legend, I hesitate to offer insight into how one should behave, but since I’m the man at the keyboard, I’ll nonetheless hazard an attempt.

For those living legends whose spheres are compact enough to have personal interactions with their most devoted disciples, I would proffer this:

Set your disciples free.

Make sure that those who view you as their yardstick of greatness know that there were failures along the way. Elucidate the mistakes, espouse your framework for decision making, and don’t be tempted into believing your own propaganda. Greatness springs from a devilishly hard to replicate cocktail of opportunity, preparation, and skill, but even when all those ingredients are present, it still takes more than a passing interaction with Lady Luck. Whether it was the woman who chose you over more traditionally appealing options or the chance conversation with a stranger that lead you to a great idea, there are inevitably moments in the story of any great mortal wherein circumstance allowed for greatness to spring forth.

As my first nephew was just born, I was thinking last week about the one wish that I would pray would come true for him. I settled on, “May his skills be suited to the era that he lives.”

Colonel Eli Lilly was the inventor who set the cornerstone of a great empire. His grandson, Eli Lilly II, was a consolidator and visionary who laid the framework for a global business from those inventions. Should Eli Lilly II have compared himself to the man from whose chemistry set created modern pharmaceuticals, he would have found himself lacking and run himself into the ground. Had Colonel Lilly been asked to set a framework for a global business, he likely would have found himself completely befuddled.

Living legends have a responsibility, an offshoot of that bygone concept of nobless oblige, to ensure that their great achievements do not hamstring their descendants with an unattainable standard. Great individuals are rare in their number but common to our species. The greatest of those individuals are the ones who ensure that their mortality is central to their story as to illuminate the reality of the possible instead of allowing an unreachable standard to become the omnipresent boogeyman of their devotees.

The older I’ve gotten, the more I realized that even within the most successful of people, extraordinarily few ever reach the Zen-like freedom from insecurity that onlookers might assume comes from their success. To be able to admit those insecurities takes a certain vulnerability. Even the greatest of men fear that their success is more fragile that most realize, or worse, that it is an outright fraud. To let one’s descendants know that insecurity lies within the breast of every mere mortal, is a gift greater than gold.

Vulnerability takes more than a bit of courage, and articulating it takes a heap time and some sustained practice. It is always easier to maintain that flawed bit of pride that says “I figured it out, and they will too.”

To truly be legendary, it is incipient upon those whose real, messy and flawed lives will eventually become the foundation for myth to let those who saw them in flesh and blood know that it wasn’t magic, and it wasn’t all roses. As Grandpa Gene used to say, “Some days chickens, other days feathers.”

Having made my daily bread for a time as a farmer, I can say with certainty that nothing grows to its potential in the shade. The size of a shadow comes not from the size of the object that casts it, but from the angle from which light is applied. If a legend truly cares about those closest to him, he must strive in word and deed to be straight with his disciples.

Everyone knows that the smallest shadows are cast at noon.